Exploring the Ruins: The Stotesbury Mansion Near Philadelphia

A Creepy (and Fortuitous) Visit Months Before Demolition

I became familiar with the “Guilded Age” as a small town kid traipsing around the grounds of Whitemarsh Hall on a hill outside of Ambler, PA. Though I lived 3.5 hours away, my closest pal Tom Troutman and I had become friends with Dean Herrick from Ambler while participating in The PA Governor’s School for the Arts. He insisted we see this glorious ruin.

The 300 acre complex built for a bank baron’s wife, and fueled, we can only imagine, by an outsized ego, floored me by its sheer size.

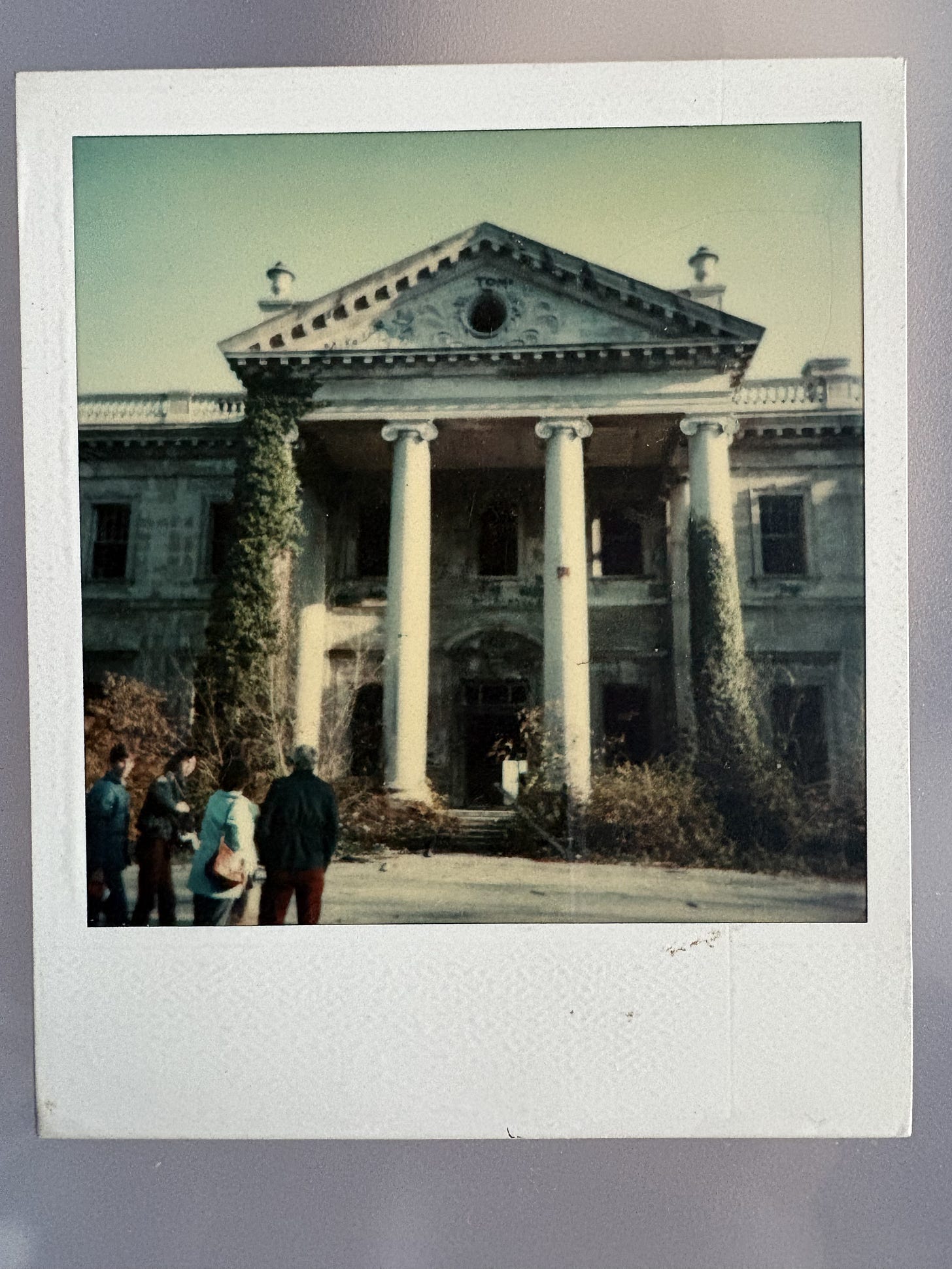

“Stotesbury,” as it came to be called by locals of Springfield Township, was designed by famed Beaux-Arts architect Horace Trumbauer between 1916 and 1921. It became a heap of rubble in 1980.

Edward T. Stotesbury built it for his wife Eva, but they barely ever stayed in it. I’m picturing that scene in Citizen Kane where the husband and wife sit at either end the football field that is their dining room table. Apparently she felt more at home in their palatial downtown mansion which now has the Instagram profile Stotesbury Mansion. It’s an event venue.1

Still Haunted

Three spooky impressions of Whitemarsh remain with me: Tales of the sub-basements, headless statuary, and, for some reason, a long servant dormitory at ground level jutting out the back of the mansion beside the gardens.

I’ll get to those, but first there are some details that remain top of mind thanks to a bevy of 35mm photos I took:

The long sewing needle of a driveway, its eye forming a looped driveway beneath a grand entrance flanked by four pillars rising up and framing a gaping round window beneath the roof’s peak.

The grand staircase, trammeled by a decade or more of local kids’ parties and early urban explorers’ pillage, seeming like a mummified widow in her besmirched funeral clothes.

One intact piece of hand-carved woodwork filigree still clinging to the horse hair plaster above a doorway.

The imprint of a Versailles-inspired garden, concrete pools, stone gazebos, and fountains to rival portions of Longwood Gardens.

A cavernous room, possibly for dining, completely ransacked and sporting jumbled racks of fluorescent light boxes dangled at random lengths from the ceiling.2

The afternoon light streaming into the second and third floor hallways through decimated windows, illuminating dust, filth, and deterioration.

Subbasements

Dean shared the legend of several teenagers who lost their lives at Stotesbury. I don’t which is scarier: The terror of plummeting through unseen holes in utter darkness or the fact that such a thing as a sub-basement exists in the first place. All I know is we didn’t go down there, no-how-no-way.

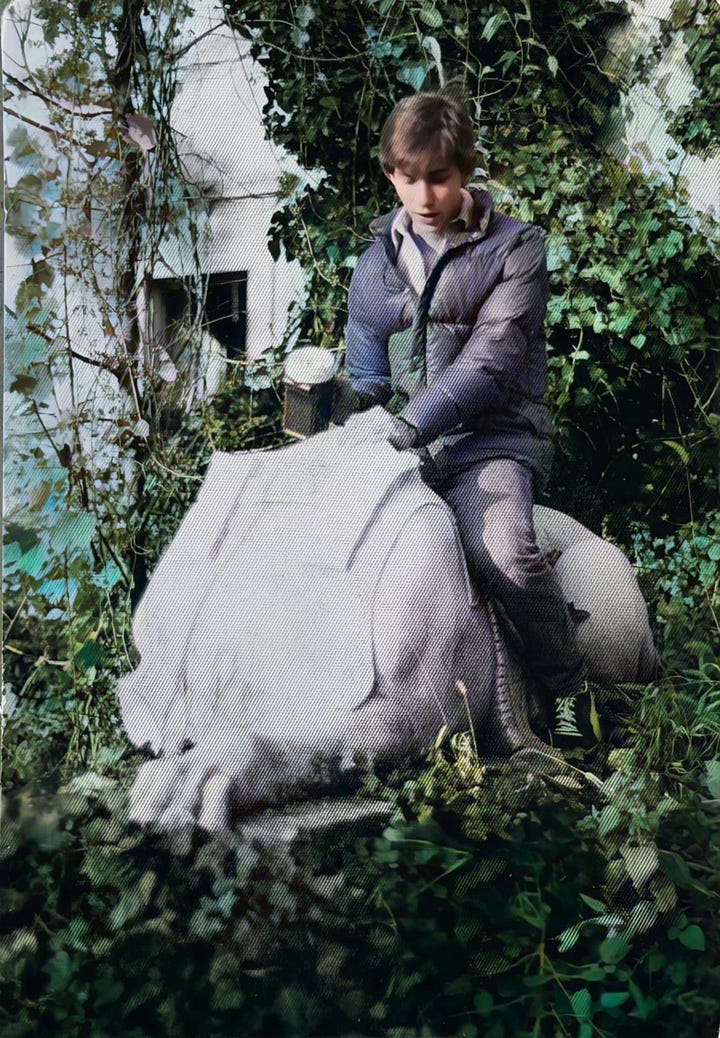

Headlessness

At some point all the local yahoos thought it would be exhilarating to knock the heads off all the marble statues in the gardens. Now, if I’m honest, and if I were a neighbor, and if I were fifteen, you might guess how I would’ve viewed such a lucky opportunity. With no heads the statuary became just like my mannequin Johnny from the Ben Franklin store who lives in my basement: Most valuable for generating heebie geebies at Halloween time. Or anytime a guest wanders down there. Poor Johnny! Lost his arms too.

Servant Quarters

Whitemarsh Hall employed 40 inside staff and 70 full-time gardeners on site. Not seven, which would’ve been a reasonable number at one of the many mansions lining Grampian Boulevard in Williamsport, PA3

Gardening, cooking, driving, serving, and what else were they doing? Who were they? What was life like in their quarters? Did they have access to the grounds and hallways, just chillin’ with the Stotes? I doubt it. It might’ve been more like a prison if they weren’t sharing in the fruits of Eddie and Eva’s opulence.

Horace Who?

After our exploration I got my hands on The Twilight of Splendor: Chronicles of the Age of American Palaces.4 It gives the full story of Horace Trumbaurer’s triumph in granite. He was a famed Philadelphia architect in the Beaux Arts tradition.

For years I owned a Xeroxed copy of the Whitemarsh chapter, carefully placed in a three-ring binder.

Horace is still with me. On a regular basis I find myself admiring two of his other architectural contributions:

The Philadelphia Museum of Art where you can still see some of the statues, paintings, and furnishings from the mansion. Four of our kids live within walking distances of that marvel.

The Bucknell University formal gate to the college. You can see it on your right just off Route 15, before the Rooke Chapel. Visits to my mother and a general pull to my homeland take me past it almost monthly.

What Happened?

A few years went by after my first urbanX adventure. I was eating lunch in the Bloomsburg University’s cafeteria working in campus ministry. I spied the backside of a T shirt showing tall pillars and a wrecking ball. I tapped the guy wearing it, and he told me he worked for the company that demolished Whitemarsh Hall in 1980. The shirt was a sort of “We won the World Series” reward.

Part of me was heartbroken to consider this grand place being pulverized and turned into townhouses. Another part of me resonated with the dense reality that a life of opulence is, in the end, a “vanity of vanities.” And yet another part of me was simply grateful to have had stomped around such a monument before it was no more.

As their Instagram post puts it

As the Stotesburys began to entertain more often, Lord Joseph Duveen convinced Mrs. Stotesbury that her “petit palais” no longer suited the grand dimensions of their new life. It was then that Mr. Stotesbury purchased 300 acres outside Chestnut Hill to build what would become known as Whitemarsh Hall. To build the estate, consisting of 146 rooms, took 83 million dollars and three years (ed.: Longer due to short supplies during WWI). Upon the completion of the home in 1921, the Stotesburys did not spend much time at the townhouse.

In 1943 Whitemarsh was bought by Pennsalt Chemical Corporation who set up laboratories where once industry magnates dined on fine china at elaborate dinner parties and not a few grim, lonely breakfasts, I surmise.

Williamsport, the city in which I was born, once boasted the highest per capita of millionaires in America. Hence, the Williamsport Millionaires public high school character/symbol/mascot.

James T. Maher, The Twilight of Splendor: Chronicles of the Age of American Palaces (Boston/Toronto: Little, Brown) 1975:1–88.

Tom- I’d agree with you on the internal conflict of recognizing outsized ego in this vanity project v. the gratitude of being able to see beauty in grandiosity. I do sometimes wonder about the point of opulence. Anyhow, great read!

This was an exhilarating read! I appreciate all the time and exploration that went into this! Excited to read more!!