An English Affair, Part the Second

I Agree with Charles: England Needs a Renewed Vision of Town & Country

[I shot the following photos on film with an Olympus 35mm in January 2020]

Lusty Gusts

A month ago I got out on my road bike. At 50 degrees, New Danville Pike felt like a damp, cold English winter. Gusts stole across the narrow road that was walled-in by hedgerows and enveloped by fallow corn fields.

A Pennsylvania boy like me might never had made the comparison if it weren’t for three memorable stays in the rural state of Hampshire; Not the “New” one here in the U.S. but the old one in the U.K.

Hampshire sits north of The South Downs, chalk hills that lead down to Portsmouth on the coast. Fifty miles southwest of London by train, it’s a glorious tangle of villages, small farms, and winding roads cut deeply into God’s good earth.

Of course, Hampshire also offers a mall in Guildford, Longmoor military range, and even a highway called the A3 cutting through all of it. It’s 21st Century England scented by millennia of history dating back to Roman and pagan times.

Imagine if the United States’ landscape were dotted with massive stone monuments above ground and intricate tile mosaics of bath houses underground. The archeology of human culture in Great Britain is, to put it mildly, rather more extensive.1

On the grounds of the manor house where we stay (I’ll talk more that about in Part the Third) sits the ruins of an 11th Century church. It was decidely planted upon the site of pagan worship. A thousand year old yew tree guards the cemetery.

On our three visits I found the village of Greatham irresistible. Walks down Church Lane are indelibly etched in my soul. Further afield, Becky and I relished the chance to knock about Petersfield, a town of about 10,000 which reminds us of our beloved home towns of Lewisburg and Lancaster, PA.

On our first trans-Atlantic flight in 1999 I was eager to see the British isles from the air due to my newfound passion for how places, particularly towns, are designed. The contrast to a domestic flight couldn’t be clearer.

The Big Bird’s Eye View

In America you fly over endless forests, deserts, or plains, that give way to a major highway paving the way for sprawling development of industry and housing. Then there’s usually a denser, historic town settled on a body of water. This pattern of thin-to-thick development reverses as you move past the populated areas.

But when you descend over the British isles, where you’d expect increasingly massive horizontal belly-bursting, there is none. Instead, you see villages and smaller towns dotting the landscape in a sea of green. London is, perhaps, an exception. The 104 mile Orbital beltway circles what is called suburbs, but even those are designed with a density that resembles old towns. Because they are basically medieval places absorbed into the urban fabric.

The post WWII New Towns movement in the U.K. has a reputation for Brutalism and blandness, a development pattern King Charles III has openly criticized for its dismissal of history, geography, and character.2 Yet even those places are ten times better serviced than our ‘burbs. Rail lines, busses, High (Main) Street shops, and open spaces make walkability a given in England. In the U.S. it’s a crap shoot.

Jane Austen Country

Traipsing around Greatham revealed to me subdivisions unlike those found in the USA: Denser and within walking distance of a community hall, the parish church, and the Old Greatham Road where you can stumble into or out of a pub without getting behind the wheel of a vehicle.

Commuting takes place up and down the A3 motorway, and some take the train to London, making Greatham partially a bedroom community but with a lot less social isolation.

Somehow 72 million people share the British Isles. Automobile transport is popular there too, but it hasn’t been the sole arbiter of how things are built or what goes where. There’s a continual cultural and political tug-of-war between transit subsidies like anyplace, but the overall tenure is that cars will not be the monarchs.

A Pub on Every Corner

On our recent trip in 2020 we stayed four nights in Brentford, a west London suburb straight out of a BBC telly show depicting middle-class life. I was struck by the sheer number of everyday people getting about on foot, to and from home.

Up until recently the Brentford Football Club pitch sat smack dab in a concentrated neighborhood behind our friends’ house. The locals could boast that at each of its its four corners sat a pub. From what I can tell on maps, three are still active: The Griffin, The New Inn, and The Brook. The team is now playing in a shinier location nearby tucked in between the M4 and 2O5 highways.

What He (the King) Said

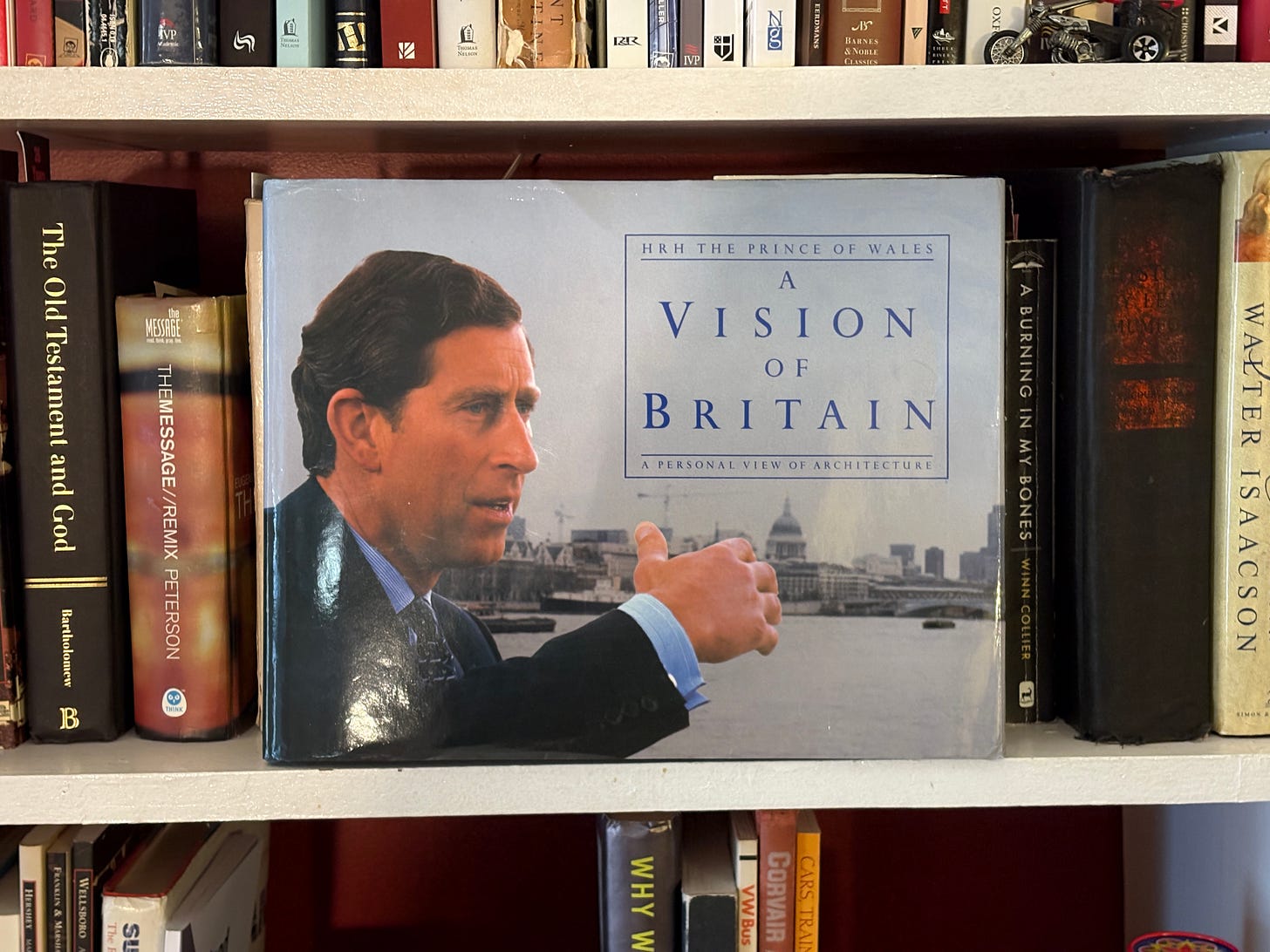

As the Prince of Wales put it in his book A Vision of Britain:

Our own heritage of regional styles and individual characteristics has been eaten away by (a) creeping cancer, and I would suggest the time is ripe to rediscover the extraordinary richness of our architectural past, as well as the basic principles which allowed our much-loved towns and villages to develop as they did.3

The now King Charles has always loved England’s built environment, and he’s not the first Brit to grieve its threatened grassroots character. His book offers a beautiful vision for taking back their land from the lustful expansion of motorways, big modern projects, and consumerist cathedrals.

I’m glad to know that he’s committed to the progress of his country not by forgetting its past but by reinvigorating what has made it so great: A nation of many yet small and strong communities…in a sea of green.

OK, So we have dinosaur bones. I’ll grant that.

HRH The Prince of Wales, A Vision of Britain: A personal view of Architecture (London: Doubleday, 1989).

HRH, A Vision of Britain, 77.